- Comfort Women

- Stories Making History

Comfort Women

Table of Contents Open Contents

Tears That Aren’t Coming

[The project to collect testimonies of Jeom-dol Jang was undertaken jointly by Gi-ja Choi and Hyun-jung Jin (former administrator of the Korean Council for Women Drafted into Military Sexual Slavery by Japan).]

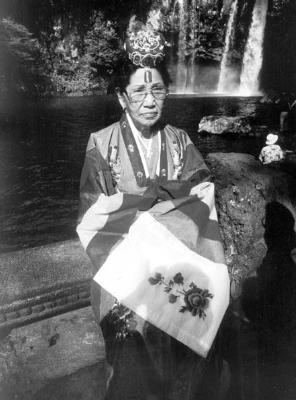

The first time I met Jeom-dol Jang was the autumn of 2002 when I joined a human rights camp held in Jeju Island with the old ladies from the sexual slavery group sponsored by the Korean Council for Women Drafted into Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. She was not part of my group and not so visible out of scores of old ladies because of her introverted character. For this reason, I was not aware of her presence until the last day of the human rights camp. It was the last day of the camp when I took some of the handicapped ladies on the last part of the itinerary. Ms. Jang was there to be photographed in full traditional wedding costume. She looked so nervous with all other ladies applauding. The council’s young male administrators volunteered for the job of being the bridegrooms of the ladies in the pictures. Although they looked happy to take the wedding pictures, I felt some sad feeling flowing from my heart. That was my first impression of Ms. Jang. She looked shy, but inside she was a strong-willed and fun-loving lady.

I met her again in November 2002 after interviews of all the other women were almost completed. There was another interviewer who visited her twice, but she was unable to finish the interview for personal reasons. So I had to do finish the work. As the lady had been interviewed twice before, she was familiar with the routine, which made it easier for me to explain what this project is about. Still, she was used to the interview style of the other administrator. It was hard for me to continue the job without interrupting her testimony. For example, I worried that I might make the mistake of asking repeatedly about something she does not want to talk about. This would cause her great pain. To not to make such mistakes, I read the transcript of the predecessor meticulously and became familiar with her stories.

But her stories were so hard to understand. It is true that not many people can tell a story of their life coherently in a chronological order. But her stories in the transcript were almost impossible to decipher in a logical order. In the transcript, she talked about her hometown and suddenly jumped to Manchuria, to which her parents went, without properly explaining when and why. And then she talked about the campaign to look for families separated during the war. She said it was Manchuria where she was taken for the first time. She described life in the comfort station in Manchuria and then abruptly turned to a story of giving birth to a baby in Singapore who died soon afterward. She mentioned another daughter who went to the United States to get medical treatment for her conditions but died in less than one year. She told a story of her life after liberation wandering here and there to make a hard living. But she jumped five decades and talked about registering as a former comfort woman with the government because she needed money. Her stories were simply a jumble that defied decipherment. The past was mixed with the present, which made me feel completely lost. On the day I was to visit her, I was so nervous. I thought to myself, “What if I make her feel bad because I can’t follow her?”

She was living in a house in Incheon with the family of her niece, whom she had adopted as a daughter. The house looked big and affluent, unlike other homes of former comfort women I had visited. But she said she was waiting for a rental apartment to be approved. She was living with her niece’s family temporarily. She was paying some living expenses. Even though she had raised the niece, she was adamant that she would never want to rely on her family. As a new welfare law was passed in 2001, the 300,000-won monthly stipend paid to her by the government’s livelihood protection program was stopped because her son-in-law had earned income. Only after the payment was reduced to 80,000 won per month did she bring herself to file her name in the comfort women registry. That is how proud she was, as she described herself. She was the last applicant to the comfort women registry as of January 2003. If the welfare law had not been revised, she would have never applied for the registry and the fact that she was forced into prostitution by Japanese imperialism would have disappeared with her death. From this, one can easily guess that there are many more “unreported” cases of sex slavery in addition to the 207 applicants officially registered with the government. For women to be forthcoming about their past as a prostitute, be it forced or not, takes a great deal of courage in this male-dominated society that inflicts pain on those who have already suffered enough.

Once the interview started, the lady rambled about her stories, jumping spatial and chronological boundaries, just like the transcript I had read. Out of frustration, I often interrupted her with questions such as “Why?” “Who?” or “When?” in the middle of her account. Fortunately, she was not annoyed by my questions and understood my intention to make the story more coherent. I interrupted frequently and rearranged the story in a logical order. At the end, the jumbled story was finally put into the “right” shape. I returned home feeling satisfied with the result.

While reading the two transcripts from a comparative perspective to compose the draft, however, I slowly realized how violent had been my effort to edit the interview. The interview transcript I took was in good chronological order, indeed. But it was something that I wanted to hear, but not a story that Ms. Jang wanted to tell me. For her, when she was born, how she was taken forcefully into prostitution, and what she did afterward were not that important. To her, what mattered more was the remembrance of her hometown, the suppressed resentment toward her older brother who took her entire family to Manchuria while she was away, and her desperate desire to meet her family again through the campaign to reunite the families separated by the social upheavals. These have nothing to do with a chronological description of events. Rather, they have more to do with family and everything related to it. In addition, the sad memory of her days after returning home in extreme poverty led to the story of her reporting with the government’s comfort women registry five decades later, and the feeling of shame in turn led to the memory of Pohang to which she could never return because of the incident with Yang and the bad rumor. The thought of Yang brought her back to the times of the comfort station. In this way, the lady’s description was a complex outcome of a process of association in her memories, rather than chronologically arranged accounts. Still, I was too used to understanding logically coherent stories, which made it hard for me to follow what she talked about. That is why I tried to rearrange her accounts in my way without considering her special thought process.

Belatedly, I regretted my mistake and tried in the draft edition to recreate her stories in her own way. First, my attempt was to unfold stories just like in movies or documentaries in which the protagonist tells a spontaneous story in flashbacks and present scenes. It was quite different from the traditional way of storytelling that is strictly based on chronological order. While movies are a form of visual art that allows showing small details without really telling the story, it is not possible in text, as there is no other way for the storyteller to explain unexplained stories. If the lady tells the reader that her family went to Manchuria while talking about her hometown, the reader might think, just as I did when I read the transcript for the first time, that she had been forced into prostitution while living in Manchuria with her family or that the family had gone all the way to Manchuria to look for her. At this juncture, if the reader sees a mention of the campaign to find separated families, how could the reader understand? For this reason, I had to take readability into account for the draft edition. Just as I understood her accounts by rearranging the fragments of her recollections in a chronological order, the reader will find it easier to understand the series of episodes in the sequential order rather than relying on association. This draft version is thus the inevitable outcome of such a rearrangement to help the reader understand better.

While listening to her stories, I felt there were many things that differed from the first impressions I had in Jeju Island, including her views on marriage and the proactive attitude toward life. Unlike my first impressions, she was kind of aloof about life, with no attachment to any relationship whatsoever. When I asked her why she did not marry, she coldly said, “I don’t envy anyone who is married.” The photographs in the traditional wedding dress in Jeju were just for fun because her friends pushed her to do it. Her aloofness was evident when she said she would not shed tears when someone close has died. She did not even cry when her own daughters died. But she admitted that she might cry if she met someone that she had known in Singapore and talked about things in the past. From this, I somehow felt that her aloofness to life originated from the days in the comfort station. To people like me, it is of little use to know how hard the life was. But with the women who went through everything together, it would be different, finally relieving her anger deep inside her heart after more than five decades. What kind of experience did the ladies there have to endure to make them frigid in their heart?