- Comfort Women

- Stories Making History

Comfort Women

Table of Contents Open Contents

“Will There Ever Be Justice?”

- Year

- Age

- Contents

- 1928

- Born in Mapo District, Seoul

- 1941

- (Age 13)

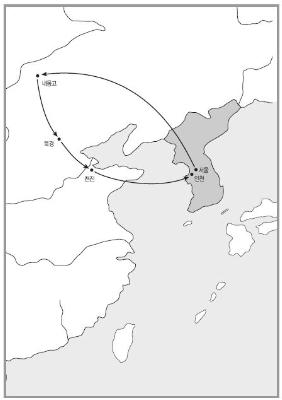

- Taken from Mapo District, Seoul, to China

Thought to have stayed at a comfort station in Inner Mongolia - 1945

- (Age 17)

- Stayed in Beijing for eight months after World War II had ended

- 1946

- (Age 18)

- Returned to Korea via the Port of Incheon

- 1950

- (Age 22)

- Fled to Daegu during the Korean War

- 1956

- (Age 28)

- Worked at a restaurant in Gangwon Province

- c. 1959

- (Age 31)

- Managed a restaurant in Waegwan, Daegu

- 1992

- (Age 64)

- Moved to Suwon

- 1993

- (Age 65)

- Registered as a former comfort woman

- 2004

- (Age 76)

- Lives in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province, with a relative

I was still young when I returned home after the war. I didn’t even want to think about marriage or just men in general. One time, a neighbor introduced me to a tailor’s son. I guess he was fond of me, because he would show up at my door every morning. I couldn’t stand the sight of him. I detested all men. I just didn’t like them – they were disgusting. I didn’t even want to think about marriage or just men in general.

I was busy just trying to live my life after having experienced such terrible atrocities. What good would marriage do for me in that state of mind?

I did feel envy toward married people. But I experienced something awful that stole my youth.”

Evasion

…to avoid conscription.

“My father passed away when I was very young. That was hard on my mother. She married when she was eleven, and she gave birth to my older brother at the age of sixteen. Then she became a widow when she was twenty-eight years old.[note 049] My mother owned a small store in Mapo. It was a general merchandise store. She worked hard, but the store didn’t bring in much money.I was enrolled in school at the age of eight, but they turned me away for being too young. My birthday was on the second day of [December in lunar year the eleventh month]. They told me to come back in netx year. When I went back after turning nine years old, they then told me I was too old [in relation to other children]. I didn’t know anything back then. I didn’t care about education at that age. So I worked as a babysitter and housemaid for other people.

My older brother was nearly [conscripted] during the Japanese occupation. My mother registered my brother independently in the family register to avoid conscription.

Even after that, she hid him under a blanket (likely in a type of crawl space) for days on end. He even used a chamber pot while in hiding that my mother cleaned out. Whatever the reason, my brother was never drafted.

My sister and I were moved from one [family register] to another and eventually ended up in our grandmother’s side so that we wouldn’t be taken as comfort women.[note 050] My sister is six years younger than me. She’s now sixty-nine years old. Our family name is Seok, but my sister is registered under my mother’s maiden name, Ahn. I’m registered as Sun-hee Ahn. But my resident registration card that I made in Daegu says Sun-hee Seok. My sister’s card still has the surname Ahn.”

Scale

The girls were being weighed.

“The Pacific War had just started. I was thirteen years old. What did kids know back then? I didn’t understand what was happening.There was a big mill in Gongdeok-dong, Mapo District.

It was the beginning of autumn. There was an announcement in the neighborhood that said to assemble by the mill. They told all girls under a certain age to show up. So all the parents gathered to find out what the commotion was about.

The girls were being stood in a line and weighed one by one on a scale for weighing grain bags. Girls who were of a certain weight were loaded on to a truck right then and there.

Some of the soldiers were armed. There were Korean soldiers, too. There were lots of Japanese soldiers and civilians. They all told the girls to get on to the truck.

I was somewhere between fifty-five and sixty kilograms (121 - 132 lbs). I was somewhat plump back then. So the men immediately loaded girls who weighed a certain amount. And I was taken, too. I was being forced in to the truck, and my mother was screaming and cursing at the top of her lungs, trying to pull me back. But none of the men cared. I think about ten or so girls were taken that day.

There were a couple of armed soldiers [on the truck bed], and a driver and another soldier were in the cab.

A black tarp covered [the truck bed], so I couldn’t see where I was being taken.

It was frightening. My heart was pounding. I didn’t know what to do. My mind was blank.”

Earthen Houses

The floors in the rooms were nothing but dirt.

“I had no idea how far I was from home. They covered up the [truck bed] and just kept driving. They also made a few stops and loaded more girls on the way to the destination. But I don’t know how far we traveled. After some time, we were told to board a train. We were at a train station. I remember the train rode over a bridge above water. The bridge was really long.I don’t know if the train station was in Korea or China, but [the soldiers] told us that we had arrived in China.

It was frightening. There were no mountains, trees, or [bodies of] water. It was a vast, yellow desert. [The soldiers] put us inside a house that was in the middle of the desert. They said some Chinese people used to live there, but they had kicked them out. The floors in the rooms were nothing but dirt. There were several earthen houses in the vicinity.

We lived in tents or run-down houses that were fixed up a bit. That’s where we received soldiers.

The desert was just stretches of emptiness like somewhere in Siberia. In other time I lived in the mountains – just tents in the mountains. One place had a bokugo (air-raid shelter). We lived there, too.

It was in the middle of the war, so wherever the troops went, the [comfort women] went, too.

I think there were about ten girls. They kept bringing more. At first there were five or six of us. Later, the number grew to a dozen or so. Additional girls were brought in a few times.”

Soldiers

They treated us like animals. We weren’t humans to them.

“[The rapes] started as soon as we got there. What did we know?An officer arrived sometime in the day. He looked me up and down, and came back later in the evening brandishing a long sword. He screamed and threatened to kill me if I didn’t obey his commands. I ran away. I hid in some hole in the ground. Then I ended up in some abandoned house. There was a chimney but no fireplace. Just a small hole big enough for me to hide in. So I hid there for a while.

I didn’t want to give them my body no matter what. If I had been caught by that officer that night, I certainly would have been killed.

There was an older girl who had been there from before I arrived. She found me and told me that I had to listen to the soldiers. That was the only way to live. I resisted and ran away many times while I was there.

They called me Yashida-san.

The soldiers would go and fight in battle and come back. Not everyone was always there.

Officers sometimes came.

It was usually quiet in the mornings, but chaos during the rest of the day. The soldiers would come right after breakfast. Those men deserve to be punished. All the soldiers who were there are probably all dead.

Saturdays and Sundays were the worst. That days basically holidays for the soldiers. I’d receive about ten men during the weekdays.

I never even saw a condom. No one even had the time to wear a condom.

The soldiers were on a schedule. They were each given a certain amount of time, so they were always in a hurry. There was no time to undress. They just put their weapons down, [raped me], and left. I remember hearing gunfire on one side, cannon fire on the other, and airplanes flying above.

I don’t remember their names anymore, but there were a few decent Japanese soldiers. One Japanese soldier just held my hand, patted my back, and told me he felt sorry for me. That’s all he did and just left afterwards. He didn’t try to sleep with me – he just left.

I started menstruating after I got [to the comfort station]. I think I was fifteen years old. But the soldiers kept coming. They didn’t care if I was menstruating or not. They only cared about sex.

The soldiers would hit me here and there, but they didn’t really beat me senseless. They would be in serious trouble if they did. There were officers crawling all over the place. The men would berate me if they felt like I wasn’t doing what I was told.

I saw two pregnant girls there. But I never saw any babies. I think someone said the babies were [aborted] at the hospital.

During the times when I was alone, I just lied there or cried from the pain and suffering. I don’t think my tears ever completely dried to this day.”

Opium

She got me started on opium.

“I couldn’t even wash my face in every day. I’d wash up only every few days. [The facilities] were awful. Every once in a while the soldiers would bring a tank of fresh water. The supplies were sparse, but we’d pour some water into basins and wash up with those.There was no underwear either. I’d wear shorts or pants – that’s it. I don’t even know how I got clothes. The girls were given dresses that resembledkimonos that opened in the front.

Rice balls for meals. There were no side dishes. We were given rice balls and that’s all we ate. There was no taste.

There were no civilians. No Koreans, either.

Money? What money?

The girls didn’t call each other by name. If someone was similar in age, she was ‘Friend,’ and older girls were ‘Older Sister.’

One of the girls was about five years older than me. I still remember her face vividly. She spoke in a Chungcheong Province dialect. She’s probably dead now – she was an opium junkie. She got me started on opium.

The way she acted, she must have been there a while. If the Japanese soldiers berated her, she would be in their faces, standing up for herself.

I would be crying day and not. One day, she told me to try smoking some opium. She said it would clear my mind. So I tried it. I’d put opium in cigarettes. I think that’s why I’m still smoking [cigarettes] to this day. If you pack cigarettes, the tobacco [becomes compacted] and a small gap is created. The girl would put some white opium powder in there. That’s how I smoked opium.

Smoking opium dulled all my senses. I’d just lie there with no thoughts. I didn’t know if something was fun or not. It was as if I was half-dead. It was a strange sensation. She taught me to hold in the hits. She said I shouldn’t just blow out the smoke through my mouth or nose. After holding in the smoke, I felt like I was going to throw up. My first time, I almost passed out, and I thought I was going to die. It was scary. I quit after a few times. It wasn’t for me.”

Syphilis

I was bleeding heavily from the syphilitic sores. I don’t even want to think about it.

“I was bleeding heavily from the syphilitic sores. I couldn’t even walk straight, so I was taken to a hospital. I received treatment, but there was no real medicine there. [The doctor] would apply some iodine [on my genitals]. My dress would soak up that red medicine … . This is why I don’t want to meet men. Who would want to share this with other people?I think I must have been fourteen years old [when I contracted the disease] – about six months after I arrived. I received lots of No. 606 injections after I contracted sexually transmitted diseases. It was called baidoku (syphilis). I got small warts (papules) all over my groin. Lots of them.... All over my lower body. I was in severe pain after coming back from the hospital. I looked at my groin and saw balls of threads. Then they would just fall off on their own.

Right here on my shins.[note 051] This disease caused a great deal of pain. [The chancres] ate away my skin – very deep. I was told that it would go down to the bone. I thought I was going to die.

There were two female nurses at the [military] hospital. The rest of the people were men. The hospital was in a big tent.

[The doctor] applied iodine and some yellow powder [on the lesions]. I don’t know how I [contracted syphilis].[note 052] This disease continued to bother me even when I was in Daegu after the war. It’s very itchy. I tried salt water, but it didn’t help. [The doctor] at the [military] hospital told me that I needed an injection of Number 606. He told me I needed it, so I complied.”

Liberation

Someone who spoke Chinese told the men that we were Korean, not Japanese.

“No one realized that the war was over. We were in such a remote location that we never saw any people other than the Japanese soldiers.[The soldiers] were being rowdy. The Japanese soldiers were acting wild, brandishing their swords.

Sometime later, foreigners came [to the comfort station]. I saw Chinese people and some westerners. It was horrific … . I get chills just thinking about it. Lots of Japanese soldiers were beaten to death by Chinese people.

[The girls] were almost killed, too. The Chinese people came running with weapons in their hands and surrounded us. Fortunately, someone who spoke Chinese told the men that we were Korean, not Japanese. We avoided being beaten to death. We thought we were as good as dead. But the Chinese people helped us after that.

A few of us stayed together while fleeing. There were no vehicles. We’d walk day and night, following Chinese people out of that area. We’d just sleep on the side of a road if we got tired, and walk continuously when we were awake. If we saw a house, we’d find some way to ask for food. This went on until we arrived in Beijing.

My feet would swell so severely that I couldn’t put my shoes on, and it was incredibly painful to walk barefoot. I think we walked for over a week.

Just thinking about the suffering, those Japanese soldiers … . I wish I could get some sort of revenge. We need justice.

I don’t know what happened to the girls that I walked with. We mostly went our separate ways. Luckily, I met a soldier from the Korean Liberation Army. He [and his wife] asked us where we were from, embraced us, and cried. They treated me well. They asked us not to go anywhere and stay with them while we were in Beijing.

[The soldier lived in] a house owned by Chinese people. The homeowner begged me to marry his son. But the KLA soldier told him that I had to return to Korea soon, so marriage was out of the question. If I think about it now, I would probably still be in China had I married that Chinese man’s son. Yes, I think so.

There were lots of soldiers from the Korean Liberation Army – always coming and going. They wore military uniforms, and hats similar to what officers wear (garrison caps). I didn’t pay them much attention. I don’t know what they were talking about, but they would always speak in secrecy.

While I stayed at that house, I helped out cleaning and cooking. The wife of the KLA soldier treated me particularly well.”

Homecoming

She was out praying for my return.

“Korea was liberated in August, but I stayed in Beijing for another eight months before leaving in April. I went to Tianjin and boarded a ship. The vessels were separated into different groups. The ship I boarded in Tianjin was enormous. I remember hearing that 3,000 people were aboard that ship.People couldn’t leave the ship after arriving in Incheon. We were ordered to stay aboard for a week. When we finally disembarked, American troops sprayed us with DDT from some big machine. They sprayed it all over our bodies and clothes.

I think there was an outbreak of diseases in Korea at the time. After being sprayed, a Korean man made an announcement on a loudspeaker for people to stay put. Adults received ₩1,000 and children received ₩500. I think I was given about ₩800. A Korean person gave it to me. That’s when the KLA soldier and I went our separate ways.

I went to Mapo in Seoul. I didn’t know how to get there. So I would walk and ask for directions. There were trolleys back then. So I took a trolley ride until the last stop in Mapo, then I found my way to Boksagol. I saw my mother returning home carrying rice cake steamers. She was out praying for my return.

I felt ill during the journey back to Korea, and I was ill for three months after returning home. It was malaria. I was sick one day and felt better the next. That went on for three months. I thought I was going to die.

I was shivering for months. Proper medicine wasn’t available back then. My mother found medicinal herbs to cure malaria take. For me she saved me.

My mother’s store had gone out of business, and she was peddling on the streets with my brother. I recovered from malaria because of her, and I had to make a living to help her. My brother was stricken with beriberi (a nutritional disorder) that made his entire body swell. I did odd jobs and worked as a babysitter and housemaid for money.”

American Army Base

My mother and I worked on an American Army base washing clothes.

“The Korean War broke out. Our family fled to Daegu to avoid the war. Sometime later, American troops arrived in the area. When the Great Naktong war was taking place. I remember the Naktong River ran red with blood – the blood of Korean troops and civilians … . It was horrific.My mother and I worked on an American Army base washing clothes. The American troops gave us all types of things.

There was a lot of food on that base. I remember seeing boxes and boxes of food. The boxes were filled with treats – bread, gum, and candy that I’d never seen before. I got to try a little bit of everything.

I found out later that it was the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps. They transported supplies all over the country.

Our family was able to eat well thanks to those people. They gave us dishes, too. Now that I think about it, those American troops gave us stainless steel silverware. They were really nice. And they gave us firearms. The soldiers told us to sell the guns for money at a market, but we turned them over to the authorities. What would we do with guns?

I was so foolish back then. I should have sold those things for money, but I didn’t think of that. If people asked for something, I’d just give it to them. I just sat there and ate what was given to me.

The American troops left when the Great Naktong Offensive was over. After they left, my family sold whatever was left at home and opened a small store. It was another general store.”

Livelihood

I used it to grind two big buckets of beans every day.

“I didn’t even get to say good-bye to my mother. She died while in Daegu, and I was in Gangwon Province at the time. I was twenty-eight years old.I had a friend in Gangwon Province. She asked me to come down, and so I did. My mother passed away shortly after that. My friend had a restaurant, and I started working there. I helped her with whatever was needed. We served food and drinks. I was there for about two years.

There was an American military base in Waegwan. My brother had some friends who worked in the cafeteria of the United States Eighth Army base during the Korean War. I was able to open a restaurant with assistance from those people and targeted customers from the base in Waegwan.

We had a big millstone at home. I used it to grind two big buckets of soybeans every day. And my arm still hurts to this day. I served soybean purée stew at my restaurant. There would be about thirty bicycles outside of the restaurant around dinner time. It was a pretty popular dish.

But I wasn’t very lucky with money. I had decided to purchase a house. I went to sign a contract for the house, but the owners had gone out to work on their farm. So I just came home. That day I ran into the butcher I frequented.

We became close, because I always went to his butcher shop to buy pork ribs for my stew. But it turned out he had a gambling problem. He asked to borrow some money. The house that I was going to purchase was ₩700,000. Back then, that was enough to buy a nice house. I lent him all ₩700,000. I think I was twenty-nine years old at the time. No, thirty-one. That’s when I came to Waegwan. Anyway, he asked to borrow money so he could purchase some equipment and cattle. A nice, big cow cost ₩200,000 in those days. The butcher was a big gambler. He ran off with all of my money. I never saw any of it again.

I owned that restaurant for about ten years. My health slowly deteriorated over those ten years, so working became too difficult.

My nephew asked me, ‘Aunt, I don’t like to see you living alone. Come to Suwon, and we can live together.[note 053] I lived with my nephew for about three years under the same roof. There were two rooms, but my nephew and his wife had children, too. I slept in the living room with my two grandnieces, and my grandnephew had his own room. My grandnephew was a senior in high school at the time. They offered to have me stay in the master bedroom. But I just couldn’t do that to them. So, I found a small room for ₩10,000,000 and moved out.

When I first came to Suwon, I worked through a local employment promotion project. I earned about ₩15,000 per day. I went to the village hall and asked for help to find employment. They found odd jobs for me through their job placement program. I had leg pains at the time, but I still walked to jobs with the help of my cane.”

Family Ties

I guess I was destined for the welfare of others.

“My niece heard the news first.[note 054] I hadn’t heard about the report. My youngest niece found out about my past. She asked her father, my older brother, about my past history. That’s when she notified the press.I guess the bonds with brother’s family can’t be severed.

My older brother is a bum – he never worked. He still does nothing to this day. It’s pathetic.

Back in Daegu, I lived together with my brother’s family. Then I lived on my own while I ran my restaurant business. Sometime later we moved in together again. But he found me again after I moved out for the last time. He’d write letters to me asking for money or a place to live.

I pretty much supported all my nephews through school. He doesn’t understand the meaning of the word ‘work.’ He’s seventy-eight years old now. He doesn’t have a cent to his name so he’s struggling at his old age. That’s why my younger sister disappeared without a trace.[note 055] My brother was an alcoholic. Now, he lives only with his wife. All of his children moved out on their own.

I don’t know why my life is this complicated. I guess I was destined for the welfare of others. My brother’s five children … . Even now, when I hear a baby crying while I am walking down a street it still feels like hearing my nieces and nephews cry. It’s strange.

My nieces and nephews are so good to me now, because I worked hard to support them. Everything I earned in my younger days all spent to feed and educate those kids. Some people don't even look after their own parents, but those kids wanted to look after their aunt.

My oldest nephew always said to me, ‘When I grow up, I’m going to live with you. I’m going to take care of you.’ And it came true. He told me that from a very young age.

I live together with my oldest nephew now. A few years ago, I nearly died a few times because of my diabetes. That worried my nephew, so we all moved in together.

My nephew used to have his own business, but after the Asian financial crisis in 1997, he had to file for bankruptcy and hasn’t had steady work since then. His wife works at a restaurant. If he wasn’t deep in debt, it wouldn’t be so bad. I just wish he could find a job.”

Hopes

I want to see this book published. I have no other wish.

“These days, my cigarettes are almost the same as my husband and children. It’s always been like this. They’re the only joy in my life. I learned how to smoke from that girl at the comfort station when I was just fifteen years old, and this habit is still going strong.I’ve cried a lot through all the suffering. I’ve spent my whole life crying. But difficulties? I’ve pushed forward by thinking to myself, ‘That’s just how life is.’

I find comfort in the mornings by listening to Buddhist chants. I’m a fake believer. I only go to a temple maybe once a month. It’s at the foot of Mt. Paldal[note 056] in Nam-mun.

These days, I spend my mornings watching television, and I go to the senior citizens’ center to play Go-Stop [a card game]. I play it with my landlord, too. Sometimes I go to the hospital.

I feel saddest when I’m feeling ill. I live on medicine these days. I eat less than babies – I have no appetite. Still, I suffer from indigestion, and so I need to take digestive medicine. Sometimes I drink [a carbonated drink] instead. My family doesn’t like it, but it really helps with my indigestion.

My diabetes prevents me from taking certain medication. Complications with my feet cause them to be numb. I hardly feel anything when I pinch them. Every part of my body aches these days. I had a major surgical procedure a few years ago. [The doctors] found a lesion on my colon. The procedure was done at Ajou University Hospital.

My only hope is to be healthy. I don’t want to be a burden to anyone. I can’t bring down [my nieces and nephews]. I just want to live in good health and die peacefully.

But things are better than ever before. I never imagined such a day would come. I’m very grateful for what you’re doing. Back then, there was no one to speak on behalf of comfort women. We were born in the wrong time. We’ve been through several wars and seen too many atrocities.

[The Japanese] need to realize that they need to atone for their crimes … . But will there ever be justice? I hope we find a solution.”

- [note 049]

- Sun-hee Seok had an older brother (b. 1924) and a younger sister (b. 1934). Her father died in 1936.

- [note 050]

- Indicates that census records for Sun-hee Seok, her younger sister, and their mother were moved from the father’s family register to the in-law’s register.

- [note 051]

- Sun-hee Seok showed three divots on her shins to the interviewer.

- [note 052]

- Syphilis can cause lesions on the legs.

- [note 053]

- Although Sun-hee Seok currently lives with her brother’s eldest son, she initially lived with his younger brother in Suwon.

- [note 054]

- In January 1992, the Korean government established the Comfort Women Issue Task Force comprised of the heads of 17 government departments and led by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Local government offices accepted registrations for former Japanese military comfort women from February 25 to June 25, 1992. Sun-hee Seok's youngest niece saw this report in the press.

- [note 055]

- Sun-hee Seok’s younger sister went missing in Daegu during the Korean War.

- [note 056]

- A mountain located in the middle of Suwon.

[note 049]

Sun-hee Seok had an older brother (b. 1924) and a younger sister (b. 1934). Her father died in 1936.

닫기

[note 050]

Indicates that census records for Sun-hee Seok, her younger sister, and their mother were moved from the father’s family register to the in-law’s register.

닫기

[note 051]

Sun-hee Seok showed three divots on her shins to the interviewer.

닫기

[note 052]

Syphilis can cause lesions on the legs.

닫기

[note 053]

Although Sun-hee Seok currently lives with her brother’s eldest son, she initially lived with his younger brother in Suwon.

닫기

[note 054]

In January 1992, the Korean government established the Comfort Women Issue Task Force comprised of the heads of 17 government departments and led by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Local government offices accepted registrations for former Japanese military comfort women from February 25 to June 25, 1992. Sun-hee Seok's youngest niece saw this report in the press.

닫기

[note 055]

Sun-hee Seok’s younger sister went missing in Daegu during the Korean War.

닫기

[note 056]

A mountain located in the middle of Suwon.

닫기