- Comfort Women

- Stories Making History

Comfort Women

“I Was Too Ashamed”

- Year

- Age

- Contents

- 1927

- Born in Busan

- 1941

- (Age 14)

- Sold to a noodle shop in Busanjin

Sold to someone in Ulsan - 1942

- (Age 15)

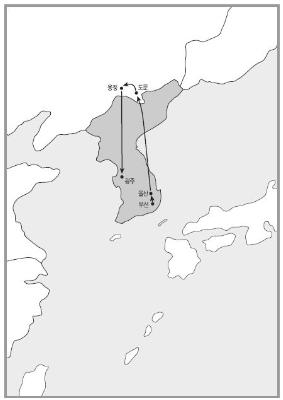

- Taken from Ulsan by the Japanese military for sexual slavery

Transported from Tumen Airfield in China to a nearby comfort station - 1945

- (Age 18)

- Married to a Mr. Shim

- 1955

- (Age 28)

- Second marriage to a Mr. Kim

- 2000

- (Age 73)

- Permanent return to Korea

- 2001

- (Age 74)

- Korean nationality restored

- 2004

- (Age 77)

- Living in the House of Sharing in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province

When I first came to Korea, I was so ashamed of my comfort woman past that I had my head down and could hardly speak. But now, I don’t have any regrets about my activities. When anyone asks me a question, I don’t hesitate to answer. Students come up to me and ask me about my past – about my experiences with the soldiers. I’ve been asked so many times now that I don’t feel embarrassed.

Students often come to visit [me for research] at the House of Sharing. My name is becoming widely known throughout the media, and I’m enjoying that. People recognize me on the street, and everyone knows me at the House of Sharing. I feel at ease. I’ve endured terrible suffering in China for fifty-eight years. When I think about that now, this is heaven in comparison.”

Desire to Learn

I was so excited. I could finally start attending school.

“I was born in Busan, but my parents were from Hwanghae Province. I was born on the tenth day of the tenth month of the lunar year in 1927. I was raised in Busan until I was fourteen years old.I would beg my mother to send me to school, but she told me that we didn’t have the money to enroll me in a school. ‘If you don’t look after your younger siblings, I won’t be able to work. Then we won’t be able to eat. So you have to take care of your siblings,’ she said. So I cried until I was fourteen years old, because all I wanted was to go to school. I would cry every year [when other kids were starting school].

One day, my mother said to me, ‘I know you want to attend school. A couple whom I know has no children, and they want to adopt you as their daughter. They’ll send you to school.’ I was so excited. I could finally start attending school.

But that wasn’t how it turned out. Since I kept begging to be sent to school and my mother wasn’t earning enough for all of us, she sold me off to some family. I ended up in a small noodle shop in Busanjin.

My hair came down to my waist at the time. When I had trouble braiding my hair, my father would braid it for me. But as soon as I arrived [at the noodle shop], they cut my hair. I was devastated. I loved my long hair. I was expecting to be enrolled in school. But I ended up working as a kitchen maid.

One day, the owner sent me into a back room. There was a table with booze…and a man was sitting in the room. He was drunk, and he started touching me. I slapped his hand away and started screaming. Since the customer started yelling, the owner came in. The man started scolding the owner, asking where he found a disrespectful girl like me and so on. So the owner grabbed me by the hair and dragged me out. He stabbed me with an ice pick. I still have a scar on my shoulder. And he beat me.

He dragged me out into the street and cursed at me for resisting a customer. He beat me and stabbed me all over with an ice pick.

Since I refused to do what they wanted, the owners of the noodle shop sold me to someone in Ulsan.

The place in Ulsan was a bar. It was a two-story building, and I was put to work as a maid. I had to work until one o’clock in the morning. I’d bring water for the customers. If they wanted tea, I’d bring them tea. I was just running a bunch of errands. I must have been fifteen years old by then.

But I didn’t stay there for more than a few months.”

That Day

I was abducted on my way back. I don’t even know who it was.

“I was kicking and resisting as someone tried to drag me down an alley. I saw a truck. They threw me in the back of the truck. I was just a young girl, and the men overpowered me. The truck drove off as soon as I was on board. I screamed for them to let me go, but they gagged me. I couldn’t talk let alone scream. There were other girls in that truck, but I don’t remember the exact number. There were five or maybe six girls. None of us knew where we were going. We ended up at a train station. We boarded a train bound for God-knows-where.We didn’t know if we were headed to China or Japan. We arrived in Tumen, China[note 057]We didn’t even realize we were in China. We were in a prison or something in Tumen. I was too young to know what a prison or P.O.W. camp was. So we went inside, and I saw sturdy metal bars everywhere, about shoulder-length apart. They shoved us into a large cell with a cold concrete floor. If I remember correctly, there were six girls. The other girls were put into one room, and I was put into another room all by myself. I still don’t remember much of what went on that night.

The next morning, all the girls that I came with had been separated. But I had no idea where they were.”

Airfield

I was cleaning the runway at the airfield.

“From [the P.O.W. camp], I ended up at an airfield.[note 058]The Japanese troops had taken over the airfield and started renovating it, because it was too small. I was cleaning the runway at the airfield.There was a barbed-wire fence surrounding the place. It was electrified. They did that to keep the girls from running away. Anyone trying to run away would be electrocuted to death.

I was taken to the base in July, so the weather was fair. We were put to work. [The comfort women] would resist whenever possible. We would kick and scream to be sent back home, so the soldiers would beat us. Some of the girls were too scared to be beaten, so they would keep receiving soldiers without saying anything. I had a bad temper, so I didn’t care. I wasn’t scared of being beaten by the soldiers. The soldiers would bust up my nose, but I just kept resisting. I would ask them why they were doing this – why they weren’t sending us home.

When we first arrived at the base, the soldiers put all the girls in one large room. But the Japanese soldiers…they were filthy animals. There would be ten to twenty girls in that room, and the soldiers would come in and gang rape the girls. They didn’t care how many people were in the room.”

Tin House

We didn’t know what a comfort station was, but we soon learned.

“The Japanese soldiers told all the girls that they were taking us somewhere. We kept resisting, so they were going to take us somewhere. We all thought that we were being sent back home, so we were excited. But we were taken to a place called the Western Market. When we arrived, I saw a big tin house, a comfort station, with a sign. We were officially comfort women. We were so naïve to think we were being sent back home.We didn’t know. Even though we got raped on the base, when the soldiers said that they were taking us somewhere, we complied. We didn’t know what a comfort station was, but we soon learned. Everyone was Japanese there. They fed us steamed millet and an awful-tasting side dish that resembled dried radish leaves. That wasn’t food. A spoonful of steamed millet felt like a spoonful of sand. It was the worst food I’ve ever tasted. But we were starving, so we had no choice but to eat. We just ate what was given to us.

We were told to entertain as many customers as possible. Weekdays were bearable, but Sundays were the worst. On Sundays, soldiers lined up in two long lines. You couldn’t see the end of the lines. We had to receive all those soldiers. How does one person receive thirty to forty men in one day? There was no time to eat. The soldiers would go into a room, but if they didn’t like what they saw, they would get angry. The younger girls would resist, or not entertain the men, so the soldiers would lose their temper and kill the girls with their swords.

The infantry wasn’t nearly as bad as the officers. We had to use condoms, but the men didn’t want to. I would say, ‘You have to wear a condom. That way you won’t get sick, and I won’t get sick.’

The names of girls were written on small wooden signs. They didn’t use our Korean names. We were given Japanese names. They called me Tomiko back then. The signs were posted on a wall. If someone was ill and couldn’t receive customers, the sign would be turned around. It meant that that girl couldn’t receive customers. But for the most part, they demanded that we receive customers. The hospitals and the military weren’t supposed to know about that. [The comfort women] had to receive customers while they were menstruating. There was some device to [circumvent] menstruations.

A little device that was designed to go in [the vaginal canal]. It was a plug - a plug to stop the bleeding (menstrual fluid). But it didn’t stop it completely. The girls couldn’t rest during menstruation. That’s why so many [comfort women] became sterile. I contracted syphilis. That was a difficult time.

Number 606 was called Salvarsan. I had lots of [injection] scars back then, but it’s gotten much better now after several decades. Some scars still remain.

I’d receive injections [of Number 606] in my arm, and they left these scars.

I received lots of shots, but they didn’t cure [my syphilis]. So I received treatments with mercury vapor.

That’s what causes [sterility] in women. [The doctor] would spray mercury vapor [on my genitals]. I’d be covered with just my head exposed.”

Bruises

I got belted until my entire body was covered with agonizing blue bruises.

“I couldn’t run away if I wanted to, and I couldn’t kill myself if I wanted to. I couldn’t buy medicine just because I had some money. I would have hanged myself if there was a tree around. In Korea, there are trees everywhere, but in China, you have to climb a mountain to find any trees. Even if you lived at the foot of a mountain, there weren’t any trees by the house. I couldn’t die, and I couldn’t escape.So I started thinking, ‘How can I escape?’ The main gates [of the tin house] opened on Sundays. I figured I’d escape [during the commotion] when the soldiers were entering. I was sixteen years old at the time. I was one year older, and I thought it was a good time to try. I actually made it out, but I didn’t know my way around China.

I had no money and no possessions. Plus, I had no sense of direction. I hid in the mountains for awhile, but they eventually found me. I was sent right back to the comfort station.

I was basically caught right after my escape. I was beaten. It’s a miracle that I’m still alive today. When I think about that moment, I really should have died from that beating. There was an ocean of blood. I was beaten by a soldier at first, but he got tired and a military policeman stepped in. He kicked me with his big military boots. When the soldier beat me, I wouldn’t give in. He’d ask me if I would try escaping again. But I wouldn’t give him the answer he wanted to hear. I defiantly told him that I wouldn’t run away if they sent me back home. I yelled, ‘Why did you bring me to a foreign place away from my mother and father?!’ I absolutely would not submit. I never told them that I wouldn’t try to escape again. So, the beatings kept coming. A military policeman was eventually brought in.

I think military police wore the heaviest boots among soldiers. After a round of kicking, he removed his belt – wide cowhide. Those belts had to hold up swords, guns, and whatever else, so they were very tough. I was belted until my entire body was covered with agonizing blue bruises. Two days after that ordeal, I had to start receiving customers again. When I undressed, the men were shocked by all the bruises and just ran out.”

Comrade Shim

He asked me to join him, and I was just happy to be saved.

“When the Japanese troops told us that we had to flee, I took their words at face value. Airplanes would drop bombs all around us, so we were naturally nervous. I assumed we were going somewhere safer. We came upon a mountain.Those Japanese troops just abandoned us at that mountain. We struggled to find our way out of the forest. There weren’t any trails for us to follow, and when the sun eventually set, we literally crawled on all fours to descend from the mountain. We found a small path at the foot of the mountain. We followed that path for some time and arrived at Yanji[note 059] city.

When day broke, we witnessed a great number of people fleeing from the area. They would hide in the mountains in the day and come out at night to eat. They would go back to the mountains in the morning. That was because [foreign troops] would come through the area in the day and create havoc. Women were raped and murdered daily. It was too dangerous for women to be out in the day. It wasn’t a good time for us to find a source of food. There were too many mouths to feed[note 060] in our group, It was a real possibility that we would starve to death. We hardly knew left from right. No one had any money, of course. At that point the group split up. I was on my own for some time.

That’s when I met Mr. Shim.[note 061]When we crossed paths, he was in a truck full of soldiers. He asked me to join him, and I was just happy to be saved.

That happened in the middle of the city. He invited me into his home. I was so grateful. I was wandering the streets of Yanji scrounging for food. So when he asked me to get on the truck, I did. The other soldiers all mocked him and laughed. ‘Comrade Shim’ is what they called him. They said that I should be Comrade Shim’s girlfriend.

I was eighteen years old when Korea was liberated. He saved me from my troubles when I was struggling in Yanji.”

First Marriage

My husband threatened to kill himself before his father’s eyes unless he gave his consent. His parents had no choice.

“When I first met my husband, he brought me to his parents’ house unexpectedly. What would any mother or father say when their son brings home a random girl? I had nowhere to go. Understandably, my future mother-in-law was completely against the idea of having a girl live with her son without being married. My husband was three years older than me. I was eighteen and he was twenty-one years old. His parents insisted that I be turned away.Mr. Shim had three sisters. The second-eldest sister now lives in South Korea. She said at the time, ‘You can’t live with this girl. Do you know why? Because this girl will never be able to bear your child. Just send her back to her hometown before you do something that you’ll regret for the rest of your life.’ [My husband] wouldn’t hear of it. When his father expressed his disapproval, my husband threatened to kill himself before his father’s eyes unless he gave his consent. His parents had no choice [but to let me stay].

My husband was still in the army at the time. He left me at his house and went back to his unit. He came home on leave a few days before our wedding date. We were finally going to get married … . But his family didn’t have much money. We couldn’t even have a wedding.

My husband was home for four days, and his friends from the army came during that time to celebrate. They stayed for two nights.

My mother-in-law was forty – no, forty-one at the time. Even though they weren’t [financially secure], she would wallow about and smoke cigarettes by a nearby brook. My husband, his grandparents, his parents, and three younger brothers all lived in one house. Including me, there were nine people living there. There were only three women in the household. Three women and six men. Despite all the mouths to feed, no one worked.[note 062] The men ate all the food in the house. There was nothing left for the women. I had to scrape the burned rice from the bottom of the cauldron. There were just too many people and not enough money.

My husband was wounded in battle and stayed home for a few months to recover. We stayed together for a few months before we split up. Why did we split up? Well, he was an officer for the Japanese army, so he could be a bit scary. He would yell at or beat his subordinates for whatever reason. They were victims of his abuse, too.

After Korea’s liberation, [there were movements to eradicate any remaining pro-Japanese factions]. People came to our house and affixed tags on all of our property [for seizing]. We couldn’t touch any of it. They took everything. I was a newly-wed bride – I had nothing. I didn’t have a thing to my name.”

Unaware

He didn’t even send a single letter. I waited for him for ten years.

“He would boast around town about how I was his woman and how much he loved me. That all changed when he left me [to go to the Soviet Union]. He didn’t even send a single letter. I waited for him for ten years. I found out later that he re-married and had children in a happy marriage. I waited for him for too long.My uncle-in-law told me that he ran into my ex-husband in a movie theater in Yanji. Younger folks’ appearances change more drastically as they age compared to older folks, you know? So my uncle-in-law didn’t even recognize his own nephew, even when my husband called him ‘Uncle.’ My husband recognized him first and asked, ‘Aren’t you from China?’ It took a minute for his uncle to realize to whom he was speaking. His uncle continued to ask, ‘Who are you? How do you know me?’ as my husband tried to jog his memory. Finally, my husband referred to his own father by name, and that’s when his uncle recognized his own nephew. His uncle asked, ‘What are you doing here? I heard you went to the Soviet Union,’ and my husband revealed that he had returned to Yanji.

So my husband invited his uncle to his house. Apparently, my husband had three daughters and his new wife was pregnant with a fourth child. My husband was asked, ‘What made you do this?’ to which he responded, ‘As a man, after I’d been living away from home for ten years, these things just happened naturally.’ His uncle said to him, ‘You’ve done wrong. You should go and see your wife back home. She’s been looking after your mother.’ My husband responded, ‘I was wrong. I didn’t think she would still be here.’

[I was oblivious] to what had transpired over the years. I had been working in a shoe factory for three years and supporting the family. Someone had to. I fed them and I clothed them. Both grandparents died while I was living with their family, and I supported them through it all.”

Second Marriage

It was a house of suffering. I wanted to hang myself.

“My aunt-in-law used to live deep in the mountains.[note 063] She asked me to come to her house for odd chores. First, I had to trim cabbages. On another day, I had to wash them. Then I had to pickle the cabbages. This went on like this for days. What was the purpose of this? My aunt-in-law was trying to arrange a marriage for me. Men would come to observe me. Right by the gate. That’s how I met my second husband. He was a member of the Communist Party of China. He was a community supervisor who enforced laws in rural areas.My aunt-in-law hid all my shoes so I couldn’t leave. She’d say, ‘My nephew isn’t coming back. It’s been ten years. He’s either not coming back or dead.’ She suggested that I marry another man. She told me that there was no need to suffer looking after my in-laws. ‘There will be no reward for taking care of your mother-in-law,’ she said. She would prevent me from leaving. Eventually, I said to her, ‘If you really feel sorry for me and want me to be happy, let me at least meet this man. What kind of man is he?’ So she introduced us, and he seemed to be a decent man. He was fairly smart. I told that man [about my past history as a comfort woman]. He responded, ‘I don’t care about that. I have two children at home without a mother. I’ll agree to the marriage if you can raise my kids as your own.’ He had an eight-year-old daughter and a three-year-old son. I agreed to the marriage.

My second husband had his share of problems. He was a heavy drinker. I couldn’t believe I was married to a man who was exactly like my father. My father gambled and he drank. He eventually sold the house, the cattle, and everything else we owned. He even gave all our rice away. I learned that much later. My brother and his wife worked hard to pay off all of my father’s debt. But we had no possessions after that. My father never gave me a thing.

It kept getting worse. All of our assets[note 064] were seized. My husband made a critical mistake. We were left with nothing.

It was a house of suffering. I wanted to hang myself. The situation was even worse than my first marriage. I had even less to eat than before. I lived with my second husband for over fifty years, and we paid off all our debts. After he passed away, some neighbors asked for donations of my husband’s clothes. When I pulled out his clothes from the wardrobe, there was a surprisingly big pile. We used to have nothing but the clothes on our backs, and I realized that we were starting to do well for ourselves. Unfortunately, he passed away before he could enjoy any of it.”

My Poor Son

I was his mother from the age of four and we lived together until he was fifty years old.

“When my husband’s first wife passed away, she left a great deal of debt behind. Their son was just three years old when I married his widower father, and he started calling me ‘mom’ within three days of meeting him. Of course, I raised him as my own. I promised myself that I would tell him about his real mother when he was old enough. The situation with my stepdaughter was more difficult, however. Girls are a little different. Since she was already eight years old by the time I married her father, and she knew the truth. She moved to North Korea after we had lived together for about ten years.[note 065] It must have been 1963 or 1964.After my stepdaughter moved to North Korea, I decided to tell my stepson that I wasn’t his mother before he turned twenty years old. I told him what happened and where her burial site was. ‘From now on, you should visit your mother’s grave, pay your respects, and look after her,’ I said. I told him to visit his mother’s family and talk to his uncle about his mother, and I bought him some alcohol to take to the grave site to pay respects. So he started tending to his mother’s grave site thereafter. He knew that I wasn’t his real mother, but he spent almost his entire life with me. He really didn’t know his real mother. I was his mother from the age of four and we lived together until he was fifty years old. To him, I’m his mother. My son and daughter-in-law are lovely people.

But I feel so bad for my son. He’s had problems with his ears and even had surgery. One of his eardrums was removed, so he can’t hear out of that ear. He could hear out of his other ear, but a lesion[note 066] was discovered. I have to yell loudly for him to hear me. That breaks my heart.

I remember staring at him when I thought about divorcing his father. ‘Who cares? He’s not my son,’ I’d tell myself. But when I thought about who would look after him after I leave, I couldn’t hold back the tears. I couldn’t do it. I just couldn’t divorce my husband.

One time, I felt that I had had enough and decided to hang myself. I went into the woods with a stick and leather strap. I climbed the mountain for a while and found an enormous [zelkova] tree. I decided that would be the place. I sat under the tree and thought about what I was going to do. ‘Should I live, or should I die?’ I thought to myself while weeping. Then I heard distant voices. My son, daughter-in-law, grandson, and my husband were all searching for me. I heard my son say, ‘She’s not here. Mom’s not here,’ and I realized then what I meant to them. I just sat there and cried my eyes out. I made a promise to myself, then and there, that I wouldn’t ever think about suicide again. I wiped away my tears and slowly made my way down the mountain. I circled the house so that they wouldn’t see me. When I got back home, I just fell to the ground and continued crying. My son rushed toward me, threw the stick away, and called to my husband. He asked me why I would even consider [suicide]. He simply said, ‘Mom, don’t do that.’ That broke my heart.”

Midwife

People still ask me to deliver their babies.

“I married my second husband in 1955. In the winter of that year, I started working as a midwife.There was no one else [to deliver babies]. The director at a nearby major hospital wondered why there weren’t any people to deliver babies. There was so-and-so and Mrs. Lee available. He wanted me to deliver babies. So, I was appointed by the hospital to learn to be a midwife. I worked as a midwife for fifteen years.

It’s not a problem for me. People still ask me to deliver their babies. In those fifteen years, I’ve never made a mistake or failed to deliver a baby.

I was in charge of sanitary work. I was in charge of sanitation; I was a midwife; I handled welfare; and I was the president of manufacturing. I had to handle four different tasks. In China, there are lots of people who take on multiple roles. When I moved to the area after the war, I was appointed as the village women’s society chief and oversaw several functions. From there, I was in charge of all the surrounding village forewomen and handled additional duties. It’s the equivalent to a women’s society member in South Korea.

Homecoming

I searched for my family for twenty years.

“I was illiterate, so it was very difficult work. But I still managed to send a letter to KBS.[note 067]But I never heard back from them.It’s been over ten years since I first mailed the letter to Korea.

I waited for several years afterwards. Then I finally received confirmation from Korea that my family had been found.

It was complicated. I worked for a Korean person in China [who owned a boardinghouse], and he had a niece. That niece’s cousin expressed sympathy for me. She said, ‘I feel so sorry for Mrs. Lee. Through her hardships, she raised her stepson as her own. She’s struggling in that house. Is there anything you can do to help her?’ There was a man from Seoul – Mr. Park[note 068]was his name. Mr. Park lived in that boardinghouse, so he knew a little bit about my history.

Mr. Park heard my story [from the owner of the boardinghouse] and came to see me.

Mr. Park said to me, ‘Is it true that you’re a former comfort woman?’ I told him that it was true. I was too ashamed to tell him any details – I just answered his question. So he told the owner of the boardinghouse he was staying in that if I wasn’t specific with my story, the South Korean government wouldn’t recognize me as a former comfort woman. I was just too ashamed to speak about my past. I just briefly gave him proof that I was indeed at a comfort station during the war.

He tried to look for my family when he went to Korea, but he wasn’t successful.

I told him that if I could go to Busan Station, I could find my house with my eyes closed. At that time, I had been living in China for fifty-five years. Mr. Park asked me if I could really find my way home from Busan Station. I told him that all he had to do was get me there.

I drew him a map of my old neighborhood. I pointed out my house and the river that I used to do laundry in. There was a bridge over that river that led to an elementary school. But it turned out that the river had disappeared. When I was young, my town was called Bosu-jeong, but apparently it had been changed to Bosu-dong. I was one word off. Anyway, I told him the directions for finding my old house in Busan and Mr. Park found my nephew. I thought my entire family would be there. My nephew then sent me an invitation [for visa approval].

When I arrived in Busan, I went to search for my house with my younger sister. She said, ‘Sister, we’re here. You said you could find it with your eyes closed.’ And I got out of the car. It had been way too long. I couldn’t even find it with my eyes open.

I arrived in South Korea on June 1, 2000. I had to stay in my room in the House of Sharing for eighteen months. I didn’t have my Korean citizenship – my family had reported me as deceased. I fought in courts, but how would a deceased person come back?

My nephew didn’t know my whereabouts for a long time, so he decided to report me as deceased. No one knew where I was. I didn’t even know where I went, how would anyone else know? So my nephew reported the death. My old neighbors told me everything when I returned. My mother prayed for my safe return every day. She prayed for my health and return every day until she passed away. My sister’s friend said, ‘I think your sister came back safe and sound because of your mother’s prayers.’

I couldn’t be happier now that I’ve returned to Korea and reunited with my family.”

- [note 057]

- Tumen is a city in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in eastern Jilin Province, China.

- [note 058]

- Ok-seon Lee was transported by train from Tumen to an earthen barracks inside a Japanese-controlled airfield in Yanji (the current site of Yanji Social Mental Hospital). (Gyeongnam Civic Solidarity Gathering for Comfort Women Issues, )

- [note 059]

- Yanji is a regional capital in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province, China.

- [note 060]

- About ten girls from the comfort station stayed together after they were abandoned by the Japanese troops.

- [note 061]

- Mr. Shim was Ok-seon Lee’s first husband.

- [note 062]

- Ok-seon Lee is implying that although the family earns money from some type of work, they are not financially stable.

- [note 063]

- Ok-seon Lee is referring to a rural area in Longjing, Jilin Province. Ok-seon Lee continued to reside in this area until her permanent return to South Korea.

- [note 064]

- As a member of the Communist Party of China, Ok-seon Lee’s second husband dealt with civil complaints from the village. Criticisms that he made while inebriated spread throughout the village and he was punished by the CPC.

- [note 065]

- According to Ok-seon Lee’s testimony, her 18-year-old stepdaughter was enticed by North Korea's migration incentives and moved there sometime in 1963 or 1964.

- [note 066]

- Thought to be a disease that causes hearing loss.

- [note 067]

- The Korean Broadcasting System television network. Although Ok-seon Lee believes KBS played a role in her return to South Korea, she in fact received assistance through the SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System) program “Events and People.” (“Korean Comfort Women in China,” Jan. 4, 1997)

- [note 068]

- Ok-seon Lee received assistance for her return to Korea from Commissioner Sang-jae Park of Yanbian University of Science and Technology in China.